A R T I C L E S & M E D I A

Some editing work in progress.

"BIJUTSUTECHO" October 12, Released on November 21, An interview with Atsushi Watanabe, connecting the emotional scars together, part 1 and part 2.

These two texts are English-translated reprints.

INTERVIEW - October 12, 2016

Part 1 of an interview with Atsushi Watanabe; the artist that “repairs” emotional scars

Artist Atsushi Watanabe previously exhibited a socially highly reviewed piece of work based on his personal experiences from time spent studying at Tokyo University of the Arts. The essence of the piece being facing up to painful situations and captivity. After graduating he spent time living on the streets and withdrew from society entirely, becoming an isolated recluse known as a “Hikikomori”, before resuming work as an artist in 2013. Having put in considerable work to create pieces of art based on his personal experiences of “Hikikomori” life, pain and depression, Atsushi Watanabe exhibited at the “Koganecho Bazaar 2016: Life - World of Asia” event and presented a new project after asking many people online to anonymously post their “emotional scars”. Through Part 1 and Part 2 of this interview we will explore the roots of the artist and this project.

Atsushi Watanabe / At the exhibition room of "Koganecho Bazaar" / Photo: Editorial department of BIJUTSUTECHO

-

This is your first time participating in the “Koganecho Bazaar” and we see you present a new project called, "Tell me your emotional scars",

which utilises the technique of “Kintsugi” (In this repair method, Japanese lacquer adhesive is used to fix broken pottery and decorative gold or powdered gold makes the cracks a

feature). Where did you get the idea to ask people to anonymously provide their “emotional scars”, go on to write them on concrete boards, smash these boards and then finally use the

“Kintsugi” process to create art?

I ended up being born as a girl. 2016 Concrete “Kintsugi” Golden Lacquer

Concrete boards smashed and fixed with “Kintsugi” Golden Lacquer. All these words were provided by people anonymously after advertising online ©ATSUSHI WATANABE

The internet was pivotal in making this project and I wanted to make something that doesn’t rely on the place it is exhibited. In the past I was in a serious reclusive “Hikikomori” state and at my previous individual exhibitions I have reached out to people in similar isolated conditions for photos of their rooms or the place where they currently live (from my 2014 solo exhibition titled, “Suspended Room, Activated House”.) The reason I thought to use the internet to ask anyone concerned to speak out or reveal their situation, was that when I was living entirely in isolation I constantly watched a show called “Niconico Live”. It was this show that made me realise just how many other “Hikikomori” there were.

Whichever broadcast I watched, comments came flooding through 24 hours a day from people obviously in a reclusive “Hikikomori” state. Although I

also was a “Hikikomori” at one time, I thought it was only me that was hanging on to life by a thread. However, I did manage to return from my “captivity” to re-join the real world. From this

experience, I felt I wanted to connect with others online (as they too might be completely isolated or in bed ill). As a result, I started this project utilising the internet around springtime

this year.

- This year you also appeared on NHK's welfare program "Heart net TV" (broadcast June 27) which featured details of the process involved in creating these pieces of art.

I thought "(The viewers of) that program probably include people currently suffering." and decided to appear. You see "Tell me your emotional scars" is a project that I want to make my life's work. I'm initially exhibiting it as installation art. Also, there are many Asian artists participating in the “Koganecho Bazaar” this time. I am currently taking steps to see if they can help spread my request for messages further than Japanese alone can using their native languages and social media connections. I hope to gather versions of the request wording in the languages of all Asian countries.

Atsushi Watanabe: taking great care decorating emotional scars with “Kintsugi” golden lacquer and a brush. / Photo: Editorial department of BIJUTSUTECHO

- Roughly when did you have the idea of using the “Kintsugi” repair technique in your artwork?

I knew it would work a long time ago when I went to a coffee shop and even though the tableware was of western design, the cracked green parts had been fixed using the “Kintsugi” technique. There was also a period when I attended a “Kintsugi” class and had the feeling that at some point I would like to use this technique in my art. With this instance of “Kintsugi” my hope is that standing alongside those who are suffering and turning their raw emotions into artwork will trigger positive change for the sufferers, ease their pain or even allow them to escape from isolation and captivity. It was these things that made me think that “Kintsugi” was an appropriate method to use.

- You use concrete in your “Kintsugi” artwork. In a performance at your 2014 solo exhibition; “Suspended Room, Activated House”, you made yourself a room out of concrete the size of just one Japanese “tatami” mat (approx. 1.6m2) and broke out of it from the inside after living in it for a week. What is the reason for sticking with concrete?

It was the case for me and I think it is the same for other “Hikikomori”, but the thickness of the wall before you reach the outside world, or the gap between the inner consciousness and the outer reality is psychologically just as bulky as concrete. At that exhibition, I made a 5cm thick wall, but I chose concrete due to the weight of my captivity, the distance or depth felt and because it is a dull color. These reasons still stand this time too.

This time his exhibits consists of 2 rooms; exhibition rooms A and B. In Room A artwork based on the replies received online lines the walls. These pieces are displayed like a tree trunk with the golden “Kintsugi” lines forming connections. Whereas in Room B people can take a look into his past, with a series of installation art pieces that recreate his experiences, such as the door he kicked in from the home he lived in when he was a “Hikikomori”, / Photo: Editorial department of BIJUTSUTECHO

- Firstly, looking back now how do you view the personal experience of being a “Hikikomori”? And secondly, have you ever imagined what kind of person you might have become if you hadn’t been a “Hikikomori”?

I originally went through a period of around 10 years of depression from 2003 to 2012. It was in the final 3 years that I completely withdrew from society. The person I am today has started enjoying living and ended up forgetting many aspects of my past psychological state. This is one reason why I did that kind of recreation style performance (at the 2014 solo exhibition).

There was a transition period of around 2 years after managing to re-enter society and I recovered in 2014. However, at the time I was a “Hikikomori” through and through and every part of me believed that I would never leave that room. That’s why now having returned to the land of the living I feel that I must use my first-hand experience to create artwork from the standpoint of someone who has suffered like me. Also, I believe that while I was a “Hikikomori” and self-harming I was in my chrysalis phase. If I can make use of the train of thought I acquired back then to put something out there and have a chance at providing someone with some positive information, then don’t you think that forms a good journey, despite having taken quite a detour? Therefore, if I had never been a “Hikikomori” and gone through depression then without a doubt my artwork would have been very different.

Picture of the 2014 solo exhibition “Suspended Room, Activated House”. “The shape of the house is sculpted in such a way that the floor resembles water and it’s sinking into the ground. This also depicts the house being swept away by the tsunami. This reclusive “Hikikomori” state, where whether dead or alive becomes questionable, is something that many people go through even in Japan’s Tohoku district where the Great East Japan Earthquake occurred. There are those who were swept away inside their own homes and others who were motivated by the earthquake disaster to stop being a “Hikikomori”. I wanted to prepare a visual depiction within the exhibition hall of this extreme situation where nature made ultimate selections and people made ultimate choices.” Atsushi Watanabe explains.

©ATSUSHI WATANABE/ Photo by KEISUKE INOUE/ Courtesy of NANJO HOUSE

- Your current “Tell me your emotional scars” process means receiving anonymous messages via the internet is necessary before work can begin to create the pieces of art. I’m sure that due to the wide variety of messages their individual impact on you varies too, but how do you feel when you receive them?

One of my assistants asked me “Don’t you get depressed or taken on an emotional rollercoaster from constantly reading about people’s emotional problems? Why do you put yourself through this?” I believe I must make sure I scoop up those who are weak or discriminated against, ensure I pick up on the emotional scars that are often overlooked when moving at everyday speed and hear the fragile voices of those who are left unheard in this noisy modern society.

For example, the meaning behind asking for anonymous messages here is that by casually reaching out to people I can create artwork that acts as a device allowing people to visualise the suffering of others, which is something I want to learn how become more sensitive to. I think that most of the emotional scars are things that you can’t say out loud. That is why I believe there is meaning in revealing these messages in the form of art. I do think that turning an idea like this into art is quite challenging for present-day Japanese society, but I am attempting it because I believe that doing things like this openly is important for the society.

Atsushi Watanabe continues to ask for “emotional scars” on his website. Also, it is possible to submit your “emotional scars” by writing them on paper provided at the “Koganecho Bazaar” event. / Photo: Editorial department of BIJUTSUTECHO

INTERVIEW - November 21, 2016

Part 2 of an interview with Atsushi Watanabe; the artist that “repairs” emotional scars

Artist Atsushi Watanabe previously exhibited a socially highly reviewed piece of work based on his personal experiences from time spent studying at Tokyo University of the Arts. The essence of the piece being facing up to painful situations and captivity. After graduating he spent time living on the streets and withdrew from society entirely, becoming an isolated recluse known as a “Hikikomori”, before resuming work as an artist in 2013. Having put in considerable work to create pieces of art based on his personal experiences of “Hikikomori” life, pain and depression, Atsushi Watanabe exhibited at the “Koganecho Bazaar 2016: Life - World of Asia” event and presented a new project after asking many people online to anonymously post their “emotional scars”. In Part 2 of this interview, we'll discuss what prompted him to become an artist, his relationship with Makoto Aida, and essential episodes from his experience as a “Hikikomori”.

Atsushi Watanabe solo exhibition "Suspended Room, Activated House" , 2014, ©ATSUSHI WATANABE/ photo by KEISUKE INOUE/ Courtesy of NANJO HOUSE

- In the first half, I asked about the project "Tell me your emotional scars," which was announced at "Koganecho Bazaar 2016", but in this half, I'd like to have you look back on what's brought you to this point in your life. At about what time did you first decide you wanted to become an artist?

It was when I was in my second year of junior high school. At that time, I saw a broadcast on NHK about students of the oil painting departments from Musashino University of Art and Tama University of Art competing to paint murals, and I could clearly see the different styles of mural painting. And I learned about the existence of art universities as well. I was a pretty fast runner from the start, so I was the head of the track and field team, my grades were relatively good, and I had a bit of talent for several different things. But when I thought about what I really wanted to do best, I eventually hit upon painting. My art teacher then was a graduate of a women's art university and she told me all about art school. Unfortunately, what I took from that was "all you do in class is art" and "you could paint pictures instead of getting a job" and I thought "Yeah, that's what I wanna do!" Ha ha ha...

- So, you liked to paint from an early age?

Starting from first grade in elementary school, I won all the prizes at art competitions and became something of a prize collector. Ha ha. Then in high school, even though I wasn't in the art club, I still managed to win a merit award at the Kanagawa Prefecture painting contest.

- Then after that, you chose Tokyo University of Art. After four failures, you started school in 2001.

A lot of art college preparation schools perform brainwashing along with their instruction that turns getting into Tokyo University of Art into a kind of categorical imperative. I got caught up in that and was convinced I had to get in. So, it was a time in which I wholly subordinated my own technique, style, and ideas to getting into that school. It was pretty rough.

- And then when you got in, was there a gap between your expectations and the reality?

I'm not good at being taught. I was taught how to hold a brush and how to mount a canvas at the preparation school, but once I started university, it was all "find your spirit as an artist" and endless rounds of creating things and having them critiqued from day one. It was hard for me to start creating art freely after I had spent so much time making things to pass a test. Yet it was still hard for me to be taught anything. I entered into a community where all I heard about at drinking parties was "your attitude as a creator" and that was what my student days were like.

Lives of Great Men of the World (3) , 2007 Oil paints and oil pastels on canvas; self-made frame; works cited panel; research file

233.6×187.3cm

Portrait of Daisaku Ikeda (President of Soka Gakkai, Japan's largest emerging religious organization ) . Presented at a graduate exhibition of Tokyo University of the Arts, published in "weekly magazine Shukan Gendai", and otherwise well-known.

- Mr. Watanabe, since you were in school, you've created works in a large variety of styles rather than aiming for a single style. Why is that?

Looking back on it now, I think it's that I don't want my hands to become too practiced. Spending four years with my face pressed against the glass of art school, I became fairly practiced at my work and I think that's why I ultimately got in. But if there is an axis within contemporary art between design and craft, then the point of contemporary art is to be ideological rather than technically refined. Thanks to my four years out in the cold, I got good at rough sketches, but it's better not to put more into a work than that. I'd like to avoid exceeding the level of technique that you might expect from your dad's DIY projects if he's decent at it. Ha ha.

Since I asked Mr. Makoto Aida to take me under his wing, I think he likely felt the same, and I sympathized with that. In some cases, he buys brushes and paints at the ¥100 shop Daiso. (He was at the Techniques and Materials Laboratory, so if there's any color to be found at a ¥100 shop that won't deteriorate, he would know.) He is conscious of the necessity of a workman not to blame his tools.

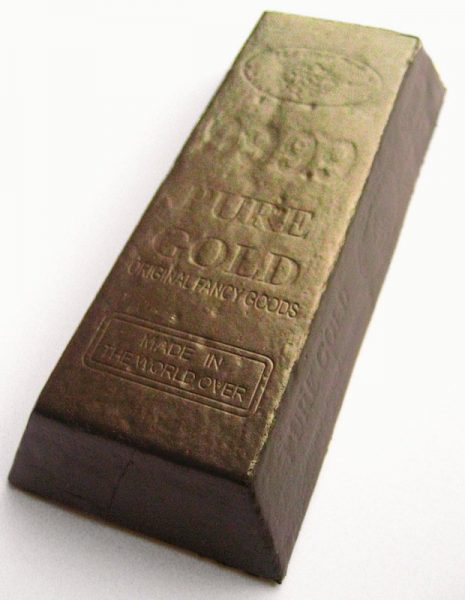

What Abety Has Yet to See, 2007 Nasal discharge (accumulated by the Atsushi Watanabe for two years), display case for gold bars placed in the vault of the Bank of Japan (reproduction), video DVD (1 min. 25 sec.), Private Collection.

First displayed at "KINCO - BoJ Walking Museum" in the underground fault of the Bank of Japan.

- Since you've assisted Mr. Makoto Aida in creating his works several times, would you say that your relationship with Mr. Aida is a significant part of your life? When did you meet him first?

That was when I was a second year graduate student at Tokyo University of the Arts, when the magazine BIJUTSUTECHO did a piece on him. At the time, I had never met Mr. Aida, yet I felt an affinity with him. When I read the feature in BIJUTSUTECHO (May 2008 issue), I thought, "I really ought to go meet this guy". I was conscious of myself not as an artist, but as a viewer and a fan. But I was afraid that meeting Mr. Aida in real life would ruin my image of him. So instead I met with every single one of the other artists who had participated in the magazine's "Blue Sky Symposium" in turn. I was afraid to meet him but I still wanted to get his aura on me.

But ultimately, I did go to meet him. I took my portfolio to show him, and he already knew my work "Lives of Great Men of the World (3)". Then, right after that, I became Mr. Aida's assistant for his solo exhibition "I'm IWAKI of Mizuma Art Gallery!!" at Mizuma Art Gallery in 2008. After that, during the critique of my graduate school completion work, Mr. Mizuma of Mizuma Art Gallery came as a guest, and as I was receiving him, he suggested that I become Mr. Aida's assistant for his long-term artist residency in Beijing. The distance between us narrowed then.

Blue Skies Symposium, as recorded in Bijutsu Techo, May 2008 issue. Participants met at the bartering café, Enoaru Café, in a "blue tent village" in a metropolitan park. With Makoto Aida as host, other participants included Misako Imamura, Ryuta Ushiro (Chim↑Pom), Ichiro Endo, Tetsuo Ogawa, Masanori Oda (Ilcommonz), Junichiro Take, Goso Tominaga, and Rena Masuyama. / Photo: Editorial department of BIJUTSUTECHO

- You admired Makoto Aida as a fan and then met him in real life. Was he different from how you perceived him?

In the Japanese art world, there's a concept of shuhari, the three stages of keeping, breaking, and then parting with tradition, and I feel like I am experiencing it as time goes on. Mr. Aida is someone that I now need to calmly overtake.

- During your time as a “Hikikomori”, did you meet with Mr. Aida or any other artists?

I didn't meet with anyone at all during the deepest part of my withdrawal (which lasted for seven and a half months), but in the two years after that (2012-'13), I did help with Mr. Aida's individual exhibition "MONUMENT FOR NOTHING" at Mori Museum of Art and other things. When you break from society for seven and a half months, it ends up taking years to get back into it. At that time, I often thought how society is made up of strong people. If you're weak, you get repelled right away. In the art world, you have to put your most extreme self out there until you make it, and to change the way you say things is almost violent, so I think it's not possible to make art with the mentality of a “Hikikomori”. So, that's why I say I've been reborn. I want to say that even a “Hikikomori” can create something, but in the art world there are a lot of (mentally) strong people, and so if you can't present your work well, you'll just be excluded.

- You said that you became a “Hikikomori” thanks to exclusion from society, but could you tell us once again what the causes were?

I had been at Tokyo University of the Arts for nine years since 2001, and I withdrew from society about half a year after I graduated. There were a number of triggers, but to put it simply, I had no place to be. I didn't have a work routine or a place to commute to, and I was nervous that I had to make it as an independent artist. I couldn't make the transition into being a pro artist smoothly. At the same time, my fiancée betrayed me and I was ejected from the protest movement I was participating in against the removal of homeless people from Miyashita Park. This was after I came into conflict with people of a feminist movement that began participating in the protest. I just didn't have anywhere to be.

- You said before, "A ‘Hikikomori’ can't make art, so the me you see right now has been reborn." I think it must have taken an incredible amount of energy to come back from your withdrawal, but what was the moment that clinched it?

About seven months into my withdrawal, my mother showed me the faintest of hints that she wanted to help me. Nevertheless, I didn't take her up on it. I didn't understand it at the time, but my mother was completely exhausted by her bad habit-ridden husband and by me being a “Hikikomori”. She didn't have any strength left. But I continued to rely on her. Eventually, I came to resent her strenuously for letting me stay the way I was even though the longer I did, the harder it would be to return to society. So, at a time when I knew she would be in the living room, I kicked down the door of the room I had shut myself into. The idea was to show her how she could open that door, by force if necessary. And I said, "This is how you get me out of here!" Then my father called the police and I was put in the hospital on a mental health hold. The situation was so extreme that it was either that or jump out the window and become homeless. I couldn't stay a “Hikikomori”. If I could, it would have just been living as a parasite to my mother. I thought I was the only one hurting, but I discovered how much my mother was hurting as well. So, I had to get out of that room.

The door, 2016 Concrete repaired with “Kintsugi” golden lacquer, paint.

Mr. Watanabe presented a reproduction in concrete of the door he kicked down at "Koganecho Bazaar 2016".

©ATSUSHI WATANABE/ photo by KEISUKE INOUE/ Courtesy of "Koganecho Bazaar"

The day I quit being a “Hikikomori” (February 11, 2011), I spoke with my mother and I took a self-portrait. If I was going to live outside of that room, it wasn't going to be in obscurity. Because to live outside of that room was to live as an artist, I had to come to terms with the seven and a half months I spent in there as unproductive time. The artists around me had spent that same seven and a half months making art with such vitality... so I tried to turn that time into something useful. Since my hair and beard had gotten long and my room was a total mess, I tried to think of it in terms of setting a scene for photography. I hit upon the idea of changing my perception of the whole affair. That moment flipped the switch on my will to live as an artist.

- Once you stopped being a “Hikikomori”, did you consider not returning to art?

Not at all. It was my goal from since junior high school and quitting art was never an option. And I think it was my fate to make works based on my experience as a “Hikikomori”, once I had come back from it.

Poster (Yellow), 2014

A self-portrait of the day he quit being a “Hikikomori”, presented as a poster. References Andy Warhol's famous quotation "In the future, everybody will be world famous for fifteen minutes."

©ATSUSHI WATANABE

- This year as you're participating in the ”Koganecho Bazaar”, you'll also be receiving the ARTS COMMISSION YOKOHAMA for the Promotion of Arts and Culture young artist assistance. Do you have some vision for what kind of work you'd like to create or where you'd like to do an exhibition having received this fund?

Well, for example, after two years or so, I'd like to do a residency abroad, and so I'm studying English ahead of time. And I'd like to be able to write up a pamphlet bilingually in time for my individual exhibition in August of this year (2017) .

- Have you always wanted to exhibit your works overseas?

It's impossible for a contemporary artist to stay in Japan forever. I don't think people will say it, but I find it urgent. There's a limit to how many people in Japan will buy your works. There's only fame here, not anything else. I think even the top artists who have the funds to hire hundreds of assistants and churn out any art they want to are currently battling on the international stage for capital... So, it's pretty important to have some element of the businessman about you. An artist can't stay an artist without planning for the future.

- If you have any plans for your next work, could you tell us about them?

Well, for example, I'm thinking of using a 3D printer to print a model of my family home, break it into pieces, and then mend it. How should I put it, maybe a concrete model repaired with “Kintsugi”... I started the habit of using one material per theme for a given exhibition before I got into the “Hikikomori” theme, so I might continue it for a little while longer while I am on this theme. So, the types of the works are completely different, but there's something that underlies them. I've got plans for several installations and pictures that, once I find a suitable design, I will make. And sometimes I'll be making things that I simply need to make, no matter how they are evaluated, based on my experience as a “Hikikomori”.

[Original text website]

BIJUTSUTECHO, October 12, Released on November 21, Kokoro no kizu wo ‘tsugu’ ateisuto watanabe atsushi intabyu zenpen kohen (An interview with Atsushi Watanabe, connecting the emotional scars together, part 1 and part 2)